The Tatshenshini Experience

The following post records the 12 days of time that our intrepid band of explorers undertook in order to raft the Tatshenshini and Alsek rivers. It is written from the pages of my personal Journal during that experience. Each day of our journey is represented and can be read individually or as a whole. Thank you for taking the time to share this experience with me. It is easily the most incredible journey I have taken into the wild.

Day 1 (9-2-16)- Driving from Haines to the north, we leave the September sunshine and stare into towering black peaks. From the silty gray level of the Klahini river to around 3,000 feet the peaks are covered in swaths of green from deep evergreen to mixed shades of yellow-green as autumn speckles the hillside along the way. There is a lot of stuff in our two little cars. One a blue Dodge Ram with a gypsy camper shell which has been retrofitted with a rolling bar on top to easily load a canoe on the roof as well as a hinged back panel, which completely removes to open the back end for quickly throwing in bags and bags of gear. The other, an overloaded Volvo from the late eighties which putters along admirably and which hasn't broken down in "at least six months." As we drive, the discussion ranges from different trips to the state of affairs in Haines, the US in general and the world. The general consensus seems to be a hell in a hand-basket type of apathy which leads me to believe that none of us will be running for president, despite the fact that "If I were president..." has been said no less than three times before we even make it the sixty odd miles to the Canadian-American border. When I ask one of my favorite questions to figure out a little more about a person, "Given a one time shot at time travel, would you go forward, or back?" Noah chooses to go forward, to my surprise, so he can "see how things shake out." Which is about all you can do.

A short, terrible, poem:

Blue sky with rain.

Pelting the window pane.

A 130 mile odyssey,

Just to catch a plane.

Day 2- We studied the entrance of the river from the put in all night by the fire, then more in the morning next to the same fire's embers while they boiled the coffee and tea needed for an early morning of rigging the boats. In the end, we went with our first instinct- a center right braid with a little extra gradient which quickly ran to deep water on river left. We meandered through classic Yukon scenery for the fall; rusty brown mountains crumbling subtly to russet and gold poplars and tall thin evergreens which give way to lush summer greens. the river was braided by never more than 3-4 channels with obvious line selection and few hazards. An easy start on a gorgeous day. As we rounded a typical left bend we went under a steel cable, signifying the beginning of the class III canyon which constitutes a majority of the whitewater for the entire 132 miles from Dalton Post to Dry Bay. The beginning of the canyon looked a bit like the S.F. Payette but with the unmistakeable gray of glacial melt running through it's steep rocky confines. The rapids came quickly between sharp corners and little room for error between rocks. The greatest hazard quickly became wrapping, pinning and broaching as the low flow couldn't produce sizable hydraulics. Jake had one brief highside, Steve found plenty of slack water for his open boat canoe (A craft that the guide book says is inadvisable, though our trip proves that an expert canoeist cannot be turned away by a guide book's understanding of canoeing ability) and Noah paddled his packraft with poise and determination. We gathered wood along the outside of a bend with the kind of eddies that only a kayaker would love, only to discover that just downstream was a massive log jam with plenty of wood for the taking and lots of calm water. Oh well, we got our haul anyway. Shortly before the unexpected sight of a jet-boat sitting on a trailer at Dollis Creek, Dana and I spotted a lynx on the shore which gave us a long once over before bounding effortlessly back into the wild. We meandered a mile down to Silver Creek where a beautiful view of the Alsek Range and a 7,800' peak covered in the whippedcream of the high alpine stood to the south with lumpy silver mashed potato clouds floating beneath a bright blue sky. It must have been around 70 degrees and I was so hot in Carharts that I took them off, along with everything else I was wearing and wandered the sheltered gravel bar naked for a while, before being spotted by Steve, who could only laugh and say that he thought of stealing my clothes. That night, by the warmth of a smoldering pile of red hot coals Jake and I watched the Northern Lights put on a beautiful green show. The vertical bars of dancing light traversed the sky like the smoke from a distant fire and trailed long graceful arcs through the atmosphere of black space and pin prick stars.

Day 3- Today we awoke to the thick frosty fog of early winter which obscured the views which stood out so vividly the day before. This soon burned off, thankfully and allowed us to defrost the many layers left out over night on dry lines. We hit the water by 10am and began a day of peaceful meandering. the land floated by slowly and huge snow dusted peaks played peek-a-boo between foreground hills covered in thick foliage at various stages of green to vivid orange. Some of the smaller poplars struck intense color battles between gold and molten orange, each leaf declaring allegiance while the maelstrom inevitably drifted toward crispy fall brown and the mushy dead leaves filled the air with the unmistakable wet dog smell of fall. The character of the river here settled into near current-less oxbows which wound in the bottom of a wide and flat valley hemmed in by rows of jagged ridges which were distant compared to the super saturated cut banks which rose along the river banks. Their soil so filled with clear water that they dripped and shone in the light like diamond cascades along their 8-10 feet of height. Eventually some tributaries (Detour / Bear Bite) added enough new flow to perk up the sleepy Tatshenshini and got it boogying down some gentle gradient. Not long down this upbeat stretch we spotted the sediments creek drainage, most noticeably its massive cobbled debris field from what must have been a biblical blowout! We pulled over immediately, wondering about our scattered pre-trip

info gathered from previous river runners who mentioned a difficult to find slough and an incorrect guide book (too old to reflect recent events). We found a wind sheltered camp on river right which suited our tastes and set up a cook fire with an expansive view to the north. Our dinner: locally caught Sockeye salmon grilled over the coals with fire toasted garlic bread sopping with butter and chunks of garlic. We ate with the kind of heartiness that comes from spending the day outside under a beautiful clear sky and were mindful to wash our hands thoroughly lest one of the big bears whose tracks could be found all over camp decided to come back that night to check out any salmon smelling people, or pants, or tent zippers.

Day 4- More blue sky and milky sunshine this morning! what luck. We began early, intending to hike a well established trail on the other side of the wash. Only 2 ended up making that journey and didn't make it back to camp until nearly noon. Jake and I hiked up the creek bed and we both were reminded of Havasu creek in the Grand Canyon. While taking in this scenery, Jake noticed a bear, which turned out to be a sow and 2 cubs upon further inspection. This sent the two of us backing away cautiously around a corner of rock so as to be out of sight of mom and her babies. After a few panicked moments of miming and fraught hand gestures, we crept back around the corner to see if they had moved. They were nowhere in sight, having slipped back into the wild which surrounded us on all sides with the grace of animals who belong in such a place.

It was a slow morning getting on the river and the river's pace reflected our lethargic manner by gently turning this way and that but eventually opened up into tricky braids and some fun change in gradient. The game changer for me was braids with gradient which was unique

and fun! After a few tributaries came in (Alkie creek) the river really dropped off into a long wavy class III rapid which turned out to be the infamous "Monkeywrench." When we pulled over at the end of the waves I was shouting it's praises but everyone else seemed rather casual about the whole thing. Most were sure that Monkeywrench was still to come and that any fun I had in the rapid had more to do with my own scattered wiring than it did with the actual joy to be had from the, in their minds, minor playfulness of the rapid. An interesting story on the name of this rapid can be found in the guide book: "This site is where the road bridge to the Windy Craggy

Mine was to be located, and the name suggests that the surveying efforts at this spot were "monkey wrenched" on a regular basis by unknown persons." Later on in the book, the Windy Craggy Mine gets another mention, hinting as to which side of the fight that the authors

of the guidebook were on during it's early days of ultimately doomed construction. "The proposed Windy Craggy Mine Project was to be located up Tats Creek and would have opened access to one of the world's largest copper deposits. The project involved massive road development into the Tatshenshini wilderness including a bridge spanning the river at the present location of Monkey Wrench Rapid. At full operating capacity, trucks would have left the mine site every eight minutes on a journey up the Tatshenshini to Monkey Wrench, across the river, back downstream to the O'Connor, onward out the O'Connor drainage to the Parton River and an eventual connection to the Haines Highway. These trucks would then follow the highway, carrying their toxic cargoes through the established Chilkat Bald Eagle Preserve, to the inside passage at Haines, Alaska. Outside of the potential hazards of that much traffic, the mine site itself posed several threats to the surrounding wilderness area. Original plans called for a highly-toxic tailings pond held back by a manmade dam. As mentioned before, the Tatshenshini is located in one of the most seismically-active areas in North America and the thought of a dam holding back a cesspool of sulfuric goo did not sound reassuring to those interested in the welfare of the area. the effects of any leakage, let alone a large spill, would be devastating to the local salmon population and the wildlife that depend on it for survival. Another Windy Craggy original idea was to dump waste material on a nearby glacier, a novel, never-before-tried notion. Imagine floating downstream past one of the most scenic and coldest waste dump sites in the world...a strange thought indeed. The folly of this project was exposed and brought to the world's attention through the efforts of a large and diverse group of people from nearby communities and international environmental groups. Hard work and excellent public relations helped bring several notable journalists and politicians down the Tatshenshini. Most, awed by its majesty and smitten with its beauty, were compelled to act. After much debate and probable political wheeling and dealing, the mine project was eventually cancelled. The momentum against the project even led to a shake-up of the British Columbia government. "On June 22, 1993, Mike Harcourt, then Premier of British Columbia, declared the Tatshenshini-Alsek a Class A Provincial Park. in 1994, the Tatshenshini / Alsek was listed as a UNESCO World Heritage Site. The new park became an essential link in protecting the entire Wrangell-St. Elias mountain Chain, creating the largest internationally protected area in the world: 8.5 million hectares, combining Wrangell-St. Elias National Park, Kluane NP, Tatshenshini / Alsek NP and Glacier Bay NP." - Lyman 2000.

We debated some about where O'Connor creek and it's camp might be since it had changed since the guide book was written and Kevin Daft (A good man to know in the Yukon) had told us just five days before that the camp was no more. We ambled down for a look see and I found it increasingly obvious that we were at O'Connor and we needed a camp quickly or we would be committing ourselves to 13 miles of the "Wind Tunnel" downstream to the next guidebook camp. My whistle didn't carry to the canoe, which was downstream and they passed a good option on the right. Noah ran a message in his pack raft and soon we were in an eddy just downstream of the potential camp and on the other side of the channel.

A quick line of both rafts put us in position for an arm straining ferry and a line up a slough of clear water into a wind sheltered and wood bestrewn beach. We were across from the magnificent O'Connor drainage and surrounded on two sides of a pointed jetty with drinkable water. It was beginning to rain in a meager way, so we set up our first cook shelter using oars, cam straps and dead man anchors to rig up a hasty shelter against the falling water. In the meantime, a fire was kicking in to gear and I decided to dry my socks on sticks next to its tempting heat. As is my nature, I put my socks closer than they needed to be and forgot them to hike up on a nearby ridge to take pictures of our camp from above. By the time I made it back to the fire my friends informed me that I'd burned one of my socks beyond repair. One down, 7 to go. The tracks around this camp were enumerable of bears big and small, moose, eagle and possibly either beaver or otter. The size and volume of tracks had us all taking plenty of precautions that night before getting into bed.

Day 5-We busted out of camp by 8:46 the next morning thanks to Jake walking around at 6:15 calling "Housekeeping!" next to all the tents and Steve banging pots and pans in the kitchen shouting "Get up! Get up! Get up!" Right away the river had our full attention with tricky

braids and increased speed with many new tributaries collecting in the main flow. One thing I love about Alaskan river running is the fun to be had on completely flat water as you read the surface of a slate gray river which covers slate gray rocks under a slate gray sky. You have to be on your toes at all times or else you'll find yourself ground out on a gravel bar which can set you back hours of toilsome drudgery to get your boat and gear to a deep enough channel to float. Sometimes the difference between success and failure is measured in mere inches, on a river system that is, at this point, miles wide. The rain definitely came on strong in the morning which sent us all into our dry suits. Within an hour on the water, the dense cloud cover began to break up, dissolve even, and shafts of brilliant sunlight pierced through to light up spectacularly the hillsides in which it could reach. As we came around the river right knob of Tats Creek we realized we weren't far from our first possible camp, Towaugh Creek. We had made it through the mayhem of braids and the infamous "Wind Tunnel" in two hours. This was faster than the estimated time during mid-summer's high water and astonishing to us. All it took was a quick shrug and a nod and we set off on another 15 miles to Melt Creek to buy ourselves another layover day at what we were told would be the highlight camp of the trip. No sooner had we agreed to nearly double our travel distance for the day than the unbelievably impressive Konamoxt Glacier of the Fairweather Ranges unveiled itself from behind swirling rain and cloud cover. We were all stunned. The black jagged ridge stood dramatically taller than the other big peaks around us and the distinct heavenly blue of the ice gave the chill of the rain more bite to already swollen fingers and cheeks. the whole moment passed in less than a minute, with the clouds closing back in around the peak as if it were not even there, but it's one minute that I'll always remember. Basement Creek came in from the left and jolted the already perky water into another gear as we began our next whitewater stretch - the S Turns. It was here that Noah went for an impromptu swim after catching a surf wave on the fly in his pack raft. The outside of nearly every bend had a wave or hole or both and the swirling current had powerful repercussions for the canoe. While Noah emptied the water from his boat, we gathered an enormous bundle of wood in anticipation of our layover day. As we rounded the final S turn and approached the suddenly wide vista of the valley we spotted a young brown bear ambling toward the river on a cobble bar. He casually strolled right up to the cut bank before lifting his head, noticing us for the first time, and bolted back the way he came at chilling speed. You could NEVER hope to out run one of these. Upon spotting the enormous 98'er creek valley we again found ourselves nearing camp earlier than we had expected. A surprise we were happy to welcome. We pulled left at Melt Creek to check our watches, we'd travelled 28 miles in under 5 hours! A celebration ensued after a fire line of gear and hot drinks were on everyone's minds. We sipped coffee, some sipped whiskey, some schnapps and stood in quiet reflection beneath an unnamed glacier clinging to the immense dark wall of the Fairweathers with the equally impressive Alsek river valley at our backs.

A few hours after making camp and still well before evening hours, I hid in my tent beneath a pitter-pattering of rain to escape the onslaught of whitesocks that swarmed rabidly around everyone in camp. Their pestering could turn a third generation, tree hugging, vegan eating, rainforest saving dirtbag into a proponent of chemical warfare and deeds most foul and lasting if it would cull the incessant horde for even 15 minutes. A small price to pay, I suppose, for a camp in the Center of the Universe—as this place was believed to be by the Tlingit people who inhabited the area for eons. The guide book gives a wonderful anecdote for this camp, "E.J. Glave, one of the first white men to descend the Tatshenhini described this area well in his article for Leslie's Illustrated Magazine in 1891: 'There is such an incessant display of scenic wild grandeur that it becomes tiresome, we can no longer appreciate it; its awe-inspiring influence no longer appeals to our hardened senses.'" - Lyman

Day 6- My notes on this day are sparing compared with the days prior. As the quote by the explorer E.J. Glave would suggest, capturing the world as viewed from this particular spot is very difficult to put into words. I took many photos this day and did my best to save as much memory of this place as I could, but there really is very little you can do to account for such a grand landscape. At one point, standing and circling 360 degrees, I counted over 30 individual glaciers. The peaks I could not count, the valleys separating these mountains were vast and yet only a subtle breeze blew and hardly a sound could be heard, despite our being camped directly adjacent to the Noisy Range. Why it is called this remains a mystery to our crew. Noah and I sat around the campfire most of the day, just taking it all in and doing the job of keeping the fire alive while Jake, Steve, Nolan, Autumn and Dana roamed the land around in search of even more interesting sights. Eventually I mustered up the energy to build a sauna from drift wood and a very large tarp. Noah and I gathered some bowling ball sized granite river stones and heaved them into the fire to bake for about 4 hours until they shone a hazy red by nightfall. These we carried in an aluminum dutch oven to the sauna to be placed in a divot in the center like a prehistoric dinosaur nest complete with egg shaped glowing rocks. When the rest of the camp returned I convinced a few into joining me in the sauna for about an hours worth of steam which finished with a high speed naked sprint to the creek and a refreshing 34 degree dip.

Day 7- The morning of our Melt Creek experience was the most jaw dropping of the trip. Which is saying something. When I pushed my rain fly out of the way my view to the East was one of shafts of heavenly light through a coastal-like cloud cover that spread out lumpily across the sky like an enormous down comforter which rested effortlessly on the very tops of the highest mountains. One of the best I've ever seen. We only boated a few hundred yards before pulling over at an island in the center of the confluence between the mighty Alsek and the Tatshenshini. The small wooded island of maybe an acre was grown well beyond its borders to the west with silt bars which afforded the most humbling view of the Fairweathers to the south, with their clinging blue ice sheets, the Noisy range to the north East, the Alsek valley to the North and the continuing Alsek river downstream of us to the west. Jake and I parked ourselves on a log while the others hunted for two small petroglyphs said to be from Tlingit inhabitants during a time in which the entire Alsek valley was under water behind a glacial moraine dam. I can now fully appreciate why they felt this to be the center of the universe. It was dead calm and eerily quiet as we sat and pondered the life of a people who were tough enough to call this place home.

Within a few minutes of pushing off the island and into the stream, we dipped our oars for the last time in the Tatshenshini's beautiful gray water and entered the oceanic Alsek river. The guide book shows flow maps for this section of river to be around 40,000 - 50,000 cfs on average for this time of year. Feeling the pull of so much current really hammered home the impressive

kayaking prowess of Dr. Walt Blackadar who was the first person to paddle the chaos of "Turnback Canyon." This chaotic Class V section is typically portaged via helicopter, but Walt kayaked the stretch during much higher flows in the summer of 1971 when he "executed a solo run of the unknown stretch of the Alsek now known as Turnback Canyon. His account of this August, highwater run down the canyon is an epic tale of near-death, disaster and survival. That solo high-water run, to our knowledge, has never been duplicated. Some kayak parties have run the canyon, but only at extremely low spring or fall water levels. it is an extremely dangerous stretch of river. To quote Walt, from his biography Never Turn Back: "I'm not coming back. Not for $50,000, not for all the tea in China. Read my words well and don't be a fool. It's unpaddleable." -Lyman

We now cruised along easily at 8-9mph through a flat expanse of gray water braided out 3 miles wide with dozens of channels to choose from at any given time which could send you careening off for an hour or more before you could meet back up with friends who happened to choose a different path. The views continued to diminish any feeling that man might be in charge or that something as tiny and fragile as a human could possibly exhibit will in a place this raw and wild. We were the mighty Alsek's willing playthings and we basked in it's immutable force.

None of what we saw thus far could prepare us for the sheer lunacy of the final bend of our day. As we rounded the aptly named (We'd find out more just how aptly by the day after) Kodak / weather corner we crept into view of the Walker glacier and its craggy friends. The mountains were pointed like obelisks of black stone with swooping saddles of ice clinging to their concave faces like blue tinted whipped cream flung from a giant spoon toward the wall. These paltry smatterings of compressed snow were trifling when compared with the behemoth of the Walker. The electrifying blue jagged snake of the truly ancient ice of the Walker glacier transfixed our attention upon its impressive dominance of so grand a vista. words were hard to come by, so most stared silently slack jawed or, in my case, snapped endless photos as our shifting position from the raft continued to roll out the view. We made camp at the foot of the glacier amid frigid wind which gave way to a lethargic downpour. The silt around camp was pock marked with enormous paw prints of a resident wolf, a few enormous bear and one rangy moose. The fog alternated between thick and thicker as Jake and I set off on a walk to the Walker, originally named because "You can walk on it!" Not anymore. In the 16 years since the guide book was first published the glacier has receded so dramatically that it would be a fool's errand to attempt to step foot on it's crevasse riddled surface. The view from the shore of the lake is still damned impressive, however. Eventually the weather lifted some and we dried out soggy gear beside a hefty bed of gleaming red coals - the work of petrochemicals I'm afraid, as the fire was not easy to coax to life in the heavy rain. This trip continues to amaze.

Day 8- [The first few soggy lines of my wrinkled notes really sets the mood for the morning of day eight]. "ooookay. Things have changed. Last night at 1am I was compelled to get dressed and get out of a perfectly warm sleeping bag to unzip the side of my wind flattened tent to make sure everything in camp was not about to blow away in the full bodied wind storm." It turns out, Jake was up with the same thought. We both careened around camp under the shaft of light emitted by our headlamps to buckle pfd's to trees, lob heavy rocks onto piles of flattened gear and tie and re-tie already secure knots on the bow and stern lines of both rafts. While this was happening, my tent became unhinged without the added weight of my sleeping body and began to tumble lumpily in the direction of the wind. I caught up to it and Jake held it down as I staked the corners back into place in a lee wind behind a boulder in the middle of camp. Jake went back to his tent, next to the boulder, and we both got back in to our soggy sleeping bags to stare at the ceiling and watch our tent poles strain torturously against the gale. My tent fly was flapping so wildly that rain could pelt my face in my sleeping bag unimpeded on its horizontal journey.

The inside of my tent began to form a puddle of a shape not unlike a glacial lake behind a moraine dam. By 2:30am I hadn't had any sleep. I periodically flipped on my headlamp just to make sure my tent poles hadn't snapped like toothpicks. During the night, Dana had to abandon

her position as her auxilliery rain tarp flew free from it's moarings and plastered itself to the alders behind her. Now fully at the rain's mercy, she decided to move her tent to a better position. This meant picking up the whole shelter and carrying it across the camp, stopping every thirty feet or so to jump into the tent during a particularly violent wind gust where she could only hold her position by laying splayed out in the manner of a starfish. This she did, several times, until her tent was positioned in the lee side of an alder thicket. While Dana was at her post, Steve had moved his tent from the river's edge, where he had been camping every night, to a similar alder thicket

which proved somewhat more sheltered than his original position. Noah and Jake, sharing a tent near mine, abandoned their spot around dawn as Noah woke to half of their tent collapsing into his face and got out to see what the problem was. The problem was they had no cover between

them and 40 mile an hour winds. He shouted to Jake to "Get up!" Because, "The tent's collapsing!" Jake, still delirious with sleep could only respond faintly with, "The tent I'm in?"

By morning the wind had not let up an inch and the rain was pelting ferociously. I moved my tent for a second time and dug a small trench on the uphill slope to divert water which streamed across the silt toward my new home. Jake came over to see if I was ok with taking an extra layover day until things "blew over." I admitted that I did not want anything to do with the river at this time. He did the same with the other tent inhabitants, waking up Steve who popped out of his tent fully clothed in his drysuit and pfd and ready for anything. Upon hearing of the layover plan, he yelled into the wind, "Well then let's get some coffee going!" Jake, Steve and I sat around the coffee urn fired up under propane power and discussed the weather like battered old seaman beneath the meager shelter of our soggy kitchen tarp. Eventually, everyone came out of their tents to have a cup and chat. We recounted our individual struggles from the night before and laughed at the various tactics displayed in order to retain control of an increasingly out of control weather situation. One by one, people drifted back to wet sleeping bags and wetter tents to wait out the storm, rising only for meals and conversation which never managed to range too far from the weather and its possibility of calming down. At a certain point, the wind almost completely disappeared and some held out hope that we might break out of camp under some sunshine and head downstream after all. This minor window of hope was soon crushed beneath another gale and pelting rain, which lasted well into the second night.

Day 9- The morning of day nine was a very special morning filled with the promise of a clear, windless day. We shoved off in record time at just after 9am to feel the current tugging at the oars again. The Walker gave us a special farewell with incredible views all the way

to its headwall. We passed glacier after glacier to the point that we stopped counting and quietly drifted past countless more. The river took a massive left and the myriad braids filling the miles wide valley seemed easier to navigate than those we saw previously. We drifted about with only minor willful choosing of channels as we neared the lake. At this point, I became antsy to get up on the river right slope to see what could be seen of our options for either entering the lake or bypassing it through "Door number 3." The entrance to Alsek lake can be doomed by the shifting positions of massive icebergs which calve off from the Alsek and Grand Plateau glaciers. These

icebergs are said to be the biggest in Glacier Bay National Park (whose domain we found ourselves under during the course of our day) as they float amid fresh water, which is less corrosive and has the added advantage of being without tidal fluctuations which break up the

big bergs quickly through jostling and collisions. As I gained elevation over the river, the sun beating down on another cloudless day, I could see the most conservative route, Door Number

3, was not an option for us as the water was simply too low. Door number 1, or "The Channel of Death" as it's also known, was free of ice at it's entrance to the lake as was Door Number 2. The troubling thing was that I could not see sufficiently around the island where we planned to camp, known as "The Knob." All I could see was a mass of ice near it's southwest shoulder and that did not bode well for being able to make it around to the south side to camp. I relayed this info to the other boats and we went up on river right again to take a look, but quickly realized that our best bet was to make a strenuous ferry back to river left to get out on the peninsula and Bear Island in order to see around more of the Knob. We made a sweaty, arm straining ferry to the peninsula and hiked over to Bear Island to take a look. The tension was high as Dana and I summited Bear Island and we could see, to our relief, that there was a large ice free channel between the

utterly massive bergs which we could use to make it to the south shore of the island. With that relief in mind, I took a moment to really inspect the surroundings from our vantage point. The steely blue icebergs floated serenely along the aquamarine of the glacier melt lake. The size of the bergs was astounding, some reaching hundreds of feet high and spanning city blocks in length. Their shapes were as singular and unique as fingerprints and the sound of their colossal icefall boomed across the water like canon fire during a sea battle in days of old. This sound, so difficult to describe but sounding nearly like the rolling of thunder would come to be a mainstay for the next two days as we camped next to these floating behemoths. With good news to share, I ran back down the mountain to tell Jake and the other boatman. We hopped in our boats and set out immediately so that the channel that was seen only moments before would still be waiting for us. We ended up taking "The Channel of Death" without consequence into the lake where a peculiar shift in group dynamics took place. Jake, having not seen the open channel Dana and I spotted because he did not get to the Bear Island summit, became quickly unsure of our plan and split from the pack to hug the shore of The Knob. This uncertainty spread to the canoe, causing Steve and Noah to abandon the lake altogether, paddling back upstream to line their boat through the puddles of Door Number 3. I, not wanting to split up further, began to follow Jake who suddenly had a change of heart in his plan, due to the increasingly tight gap between a huge ice berg and the Knob, and coaxed him into the center of the lake again to the channel which I knew would appear if we could only get around the first ice bergs and their limiting line of sight. Eventually we did spot our enormous ice free body of water, and we pulled hard between the gatekeeper icebergs like pedestrians crossing an oncoming train's track. These trains moved not an inch, though their fickle nature and aptness toward rolling over like corks to reveal acres of ice beneath the water gave us all the energy we needed to pull hard to the south shore and I kissed the ground when we landed. During all of this, the calving glaciers at the far end of the lake sent 10 story tall hunks of ice into the water with a sound like dilapidated high rises being professionally blown up by demolition men. The ripples of these huge displacements of water came to shore at our camp every now and then, reminding us that the water which seemed so calm now could at any point fill up again and block us off from our route out of the lake.

Soon after we made landfall, the canoe popped out from the other side of the Knob and we rejoiced with a big fire and more hot drinks. As the sun set to the west, the Fairweathers burned with a pink and purple alpenglow which began on the 15,000 foot summit of Mt. Fairweather and

drifted into a starry black night.

Day 10- Our final layover day was restful though torturously buggy. The worst bugs of the whole trip in fact. Noah and I took the canoe for a spin out among the ice and paddled across to a particularly beautiful piece that I'd spotted from shore. As we navigated around the eerily

calm garden of ice and stone the distant crack and roar of calving ice kept us well away from the bobbing skyscrapers. One piece sat at a gentle angle from the water to a height of about 80 feet in a cheese wedge shape. We chatted casually about how it would be fun to walk up it and

gain some higher ground amid the ice bergs. An hour later as we were checking out a beautiful sculpture, a piece the size of a two story house sheared off the berg we had been tempted to walk up before. The ripple created a riot of noise which shattered the calm of before as the waves slapped and smacked the pocked and fissured subsurface of the ice. For a few long minutes we sat in the canoe in open water waiting for the seemingly inevitable sympathetic reaction from the rest of the armada but nothing came of it and peace was once again restored amid the mirror-like finish of the water. We returned to camp like two wayward tribesman with strange stories of stranger lands. Everyone eventually took the canoe for a stroll to feel the power of the icebergs for themselves. After an afternoon siesta which was little more than an excuse to hide in my tent from the incessant bugs, Jake and I hiked to the top of the Knob to take in the lake from above. The split tongue of the Alsek glacier loomed from across the water and we estimate that the face is roughly 150-200ft of vertical, rock hard, ice. Near the left route pieces of ice a few acres wide drifted lugubriously out into the lake, only time will tell for how long they will float before coming around to their liquid form again, a state they haven't taken for thousands of years. Hiking north across the island took us to another view of the 3 mile wide braided force of the Alsek river as well as the delta where it spills into the lake to mix its gray water with the turquoise blue of the lake. At the river mouth we could see an iceberg the size of a pair of school buses side by side moving at great speed in the current at the mouth of the river. If we had come out of the river as this piece outpaced us into the lake, we would have been even more terrified than we already were. It's scary enough when they're looming stationary, it's quite another level of insanity when they're moving faster than we can row. The melancholy of the final night on the river was in full effect by this point. I may never again fall asleep to the sound of thousands of tons of ancient ice cracking off from a great height into a lake of pure glacial water. This trip cannot be properly explained or understood with something so insufficiently visceral as words and photos. It is a beauty to behold and a memory to be held onto. Someday when I'm old and used up, at least i'll have this to reminisce upon and realize that I've really done something special with my time. I don't want it to be over. I already long for the simple pleasure of wondering what's around the next bend.

Day 11- On the way out of the lake we came through our final stretch of current, the Lower Alsek River. On this flat cold water I got the opportunity to do something completely unique. I got to row a rapid formed by grounded icebergs! As we came closer to the waves of what looked at first to be rocks we discovered huge icebergs covered in moraine debris kicking out some of the finest waves I've ever seen. It had me longing for my kayak so I could turn upstream and surf these 6-8 foot standing green waves with frothing piles of foam dancing at their crest. Breaking this lateral set you up to crush some big compression waves downstream which I eagerly began rowing to. Noah, clad only in rain gear, was not keen to hit the waves bow first, so I had to pull into them and drenched the stern of the boat on a few truly awesome waves. We came out a little colder and a little wetter, but I felt it plenty worth the novelty. Just as we passed the final feature of the river the rain came on like a faucet and pelted us mercilessly thanks to an icy wind. As soon as we hit the beach, we de-rigged in record time and fled for the shelter of an upwind alder thicket which served as temporary shelter from the storm. We hunkered down and ate some snacks while waiting for a rain gear clad Alaskan by the name of Pat Pellett to arrive on ATV to pluck us out of nowhere and take us to somewhere. We loaded up our gear for two trips on the ATV shuttle and handed over 350 bucks for the service. Not a bad way to make a living, if you don't mind the peace and quiet. He brought us to the airstrip and food cache, pointing out the pit toilet, the first toilet not bucket shaped we had seen for 11 days, and left us to weather out the storm until the next day when our plane would come roaring in at noon. By 2 o'clock, we had reached our final destination for the day, a 12x8' wooden food cache built by the park. The cache was originally built to store food after trips so that bears would not be tempted to come around the takeout and accompanying airstrip. In reality, boaters pile all of their gear together in the rain while waiting for their plane and hunker down in the cache to play cards and talk about their amazing trip experiences. The ranger that works here, as this is the northern tip of Glacier Bay National Park, explained to us that this was about the most desolate and lonely station in the park service. He seemed happy with it and was relieving a park ranger who had taken a higher position in the same area after 23 years on duty here. We gave him some left over oranges, which he seemed happy to accept, and left him to motor around his little woody oasis on his government ATV in the thick of a rain storm. I curled up in the corner of our smelly little cabin and began a book that has been one of my favorites for years, despite having only read it once, Slaughterhouse Five, Or, The Children's Crusade. By the time the plane arrived the next morning, I scanned the final sentence, thoroughly impressed once again by the wit and candor of Kurt Vonnegut.

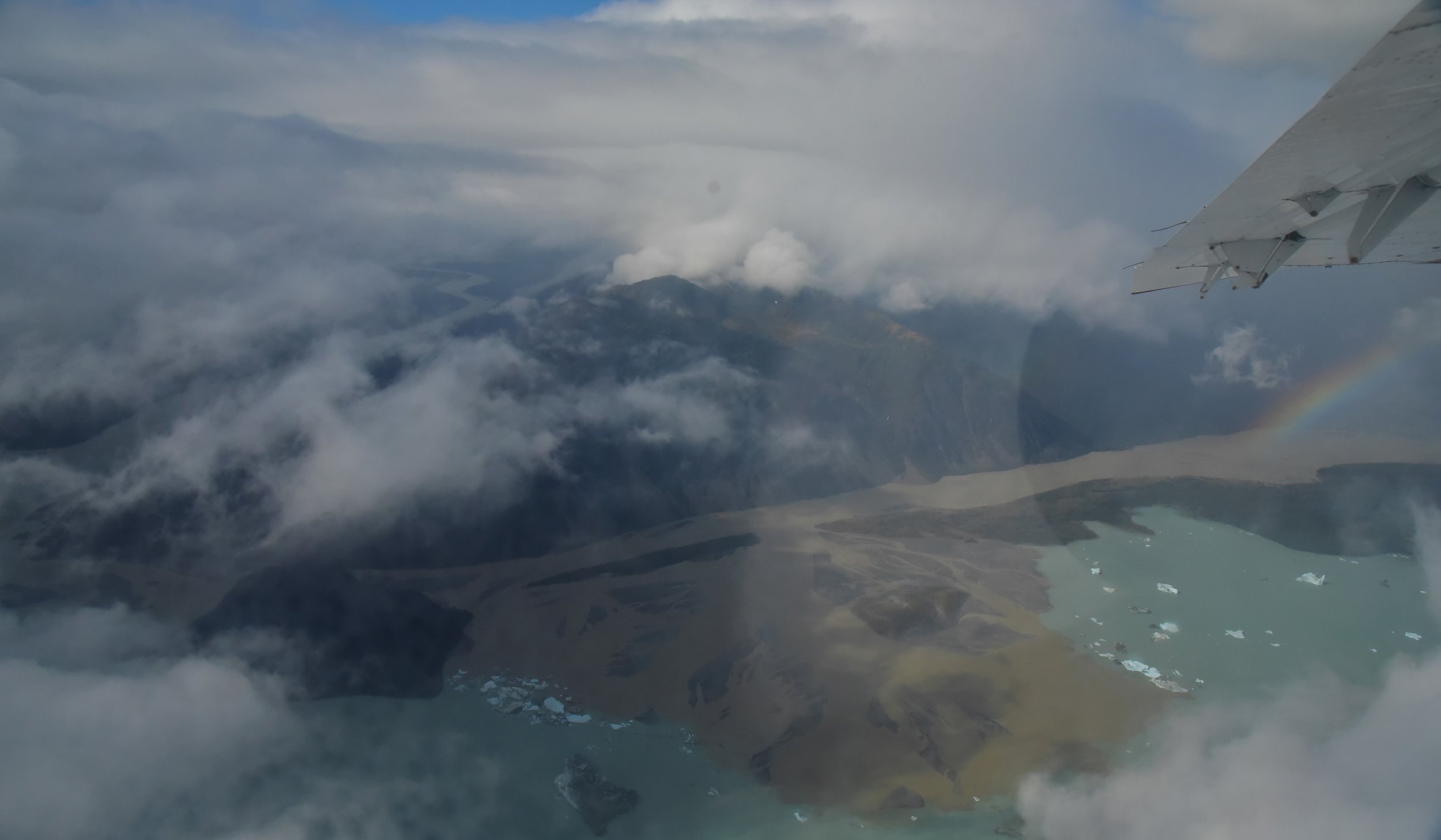

Day 12- After a stormy night in the shelter at the Dry Bay Airstrip and Luxury Hotel, we gathered our belongings in anticipation for a noon flight which was still up in the air (pardon the pun). When the plane did show up, we packed it in a hurry and were airborne within 15 minutes. The flight was amazing yet slightly terrifying as we hit wing rattling turbulence while diving into the thick cloudy ceiling over the final ridge coming in to Haines. I began making a plan in case of our being stranded on a glacier with only half a plane and some survivors. Noah gripped the aluminum raft frame packed in front of him with white knuckles, cheeks puffing, eyes down and closed to the point of creasing. Then, we popped out over the familiar Chilkat river and all was well again. We chucked our gear out of the plane onto the tarmac of the airport in an out of the way corner and crossed our fingers that the Volvo would start and be able to grab Steve's truck for all of our gear. Some pulled out cell phones to make plans for the next leg of their journeys, some simply sat on the pile of gear as though it were the spoils of war, a far off look in their eye and a buddha's smile on their lips. We all basked in a radiant happiness that had clearly sunk in deep. The final piece of my journey involved a ferry ride back to Skagway and a van waiting at the dock with my lady, our two dogs, and a fresh hot pizza. Perhaps the only things more inviting to me than the wilderness we had just been released from. In the words of the esteemed Bart Henderson, "Enjoy it, respect it and protect it."